Eleanor Spencer

Sustainable Business Specialist (Asia)

The boundaries between planted monocultures and more natural vegetation growth are always striking. Whether you’re seeing vast fields of rapeseed giving way to scrub and grasslands, or industrial tree plantations wedged tightly against tropical forest; the contrast between the uniform monoculture and messy, vibrant natural habitat, is often stark. It serves as a useful reminder not only of the diversity that may have been there before the plantation, but also of the vital importance of the remaining habitat in comparison.

I’ve been reminded a lot of this importance recently on visits to oil palm plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia. In one case, in a brief break between meetings, we stepped outside to find not one but two species of Red List langur species just a few metres from us, in the conservation area next to the company’s office. I watched them feed and play for a bit longer than I meant to (watching endangered species seems an acceptable excuse for delaying a meeting about biodiversity), and thought about the crucial role of even this small patch of forest – set aside by the company in its development – in helping threatened species cling on within a monoculture-dominated landscape.

The loss of wildlife in the tropical belt

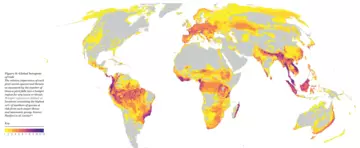

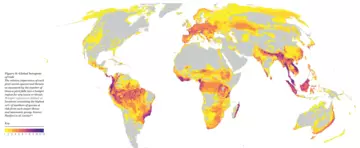

The Tropics – the regions concentrated around the Earth’s Equator – are home to the some of the highest concentrations of terrestrial biodiversity on the planet. Therefore, plantations and concessions for soft commodities produced in tropical regions – such as palm oil, timber and pulpwood, and natural rubber – are usually located in areas that are also potential habitats for a huge variety of wildlife species. In many cases, industrial-scale plantations are occupying land that has been cleared of its natural vegetation only within the last 50 years.

That period has been particularly disastrous for wildlife. The Living Planet Index (LPI), produced by WWF and ZSL, is a measure of the state of the world's biological diversity based on population trends of vertebrate species from terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats.

The latest LPI, published in 2022, shows clearly how wildlife populations have plummeted, with an average decrease of 69% in wildlife populations between 1970-2018. These losses have all been greatest in the regions within the tropics, and by overlaying data on over 23,000 IUCN Red List species with data on six key threats, including agriculture, we can see that wildlife in the tropics is under particularly strong threat.

Among the key drivers of biodiversity loss in these regions are habitat loss and degradation. Land clearance for the production of soft commodities has had a significant role in this. According to a 2021 study, an estimated 15.8 million hectares of forest were lost in Southeast Asia between the years 2000 and 2015, and approximately 9.4 million hectares of that is now cropland. These crops are often grown in a monoculture – close to a 100% reduction in plant species diversity at that site – which drastically alters the ecology of the area and reduces the variety of wildlife able to survive there.

The importance of conservation set-aside areas

However, in recent years there has been a lot of change in these industries’ approaches to sustainable production, with many companies committing to zero deforestation and setting aside conservation areas within their concessions, through either their own policies or external certification schemes. These include riparian buffer zones around rivers and other water bodies, and areas with High Conservation Value (HCV).

The latest SPOTT assessments suggest that many companies in key forest-risk sectors are on board: notably, 67.5% of palm oil companies and 64.7% of natural rubber companies assessed have publicly committed to zero deforestation. However, the timber and pulp industry has more room for improvement, with just over half of the companies in the 2024 assessment publicly committed to this goal. Regarding HCV assessments, an average of 63.7% of companies assessed on SPOTT publicly commit to conducting these for all new development and planting.

High Conservation Values (HCVs)

The concept of ‘High Conservation Value’ (HCV) areas was first used in forestry, but is now widely implemented across various soft commodity sectors, and is a key component of several voluntary certification schemes, including the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

The HCV approach is a practical tool for identifying and protecting biological, ecological, social and cultural values ‘of outstanding significance or importance’ in production landscapes, and incorporates a precautionary approach and consideration of the wider landscape context within which HCVs are identified. There are six categories used to classify HCVs:

HCV 1: Concentrations of biological diversity, including rare, threatened or endangered species

HCV 2: Landscape-level ecosystems and mosaics, including intact forest landscapes

HCV 3: Rare, threatened, or endangered ecosystems, habitats or refugia

HCV 4: Basic ecosystem services in critical situations, including water catchments

HCV 5: Sites and resources fundamental for satisfying the basic necessities of local communities or Indigenous peoples

HCV 6: Sites, resources, habitats and landscapes of global or national cultural, archaeological or historical significance

The HCV Network is a member-based organisation that oversees development and coordination of the HCV approach, providing guidance and quality-checking.

These conservation areas within company land can be of huge ecological importance, often providing the last refuges for rare species within highly modified landscapes, or acting as vital connecting corridors between forest patches, allowing wildlife to still move through the landscape. These benefits are generally more significant the larger the HCV area, and the more connected it is to other natural habitats nearby – research from the SEnSOR programme suggested that a minimum 'core' patch size of 200 hectares is important for HCVs to have significant biodiversity benefits, with the potential to support 60-70% of the species richness in continuous forest in the same area.

Based on the latest SPOTT data, ninety-nine out of 230 companies we assess across the palm oil, timber and pulp, and rubber sectors, report that they manage over 6.8 million hectares of company-owned land set aside for conservation. This is a huge area of land for wildlife – greater than twice the combined land areas of Gunung Leuser, Kerinci Seblat, and Bukit Barisan Selatan National Parks in Sumatra, which collectively are home to an estimated 10,000 plant and 200 mammal species. Of course, these 6.8 million hectares are fragmented into small patches spread across multiple landscapes, countries and continents, but if managed well and connected with other patches where possible, they arguably hold significant potential for biodiversity conservation in the tropics.

Effective wildlife monitoring and management by companies

The companies managing these lands therefore hold a huge conservation responsibility, and it is essential that they are sufficiently equipped and supported to conduct effective biodiversity monitoring and protection.

Monitoring and management of company conservation land is a common requirement – and a requirement for HCV areas under certification schemes such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). However, the methods used and expertise required for monitoring and managing conservation set-aside areas are not generally very prescriptive. There is a not a standardised approach to monitoring and protecting species across industry sectors, or across the same landscapes.

As a result, the quality of the data collected, and therefore its value for informing conservation action, varies a lot between geographies, sectors, companies, and concessions. Many companies are now putting significant resources into conservation in their concessions and are keen to ensure their actions are effective, but are unsure how to go about this and where to go for support.

How we can help

ZSL is an international scientific institution with decades of experience monitoring wildlife and running conservation projects across Europe, Asia and Africa. Our efforts range from working with the private sector to increase ESG disclosures of soft-commodity companies, to hands-on conservation fieldwork, such as helping to reintroduce the scimitar-horned oryx to Chad - a species that became entirely extinct in the wild in 2000.

ZSL works at the interface between conservation and private-sector activities, and is well-placed to bring scientifically rigorous data and approaches to companies operating in tropical commodity sectors. In recent years we have been doing just this, by rolling out our advisory services on biodiversity monitoring and management support.

Ways we can support:

- Helping the private sector understand why biodiversity protection is integral to the future of their businesses, and not an ‘add-on’ ESG category

- Providing direct support on biodiversity monitoring survey methods, technologies and tools

- Support in analysing data, including management and analysis of camera trap data through our proprietary Camera Trap Analysis Package (CTAP)

- Support on implementing the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) approach

A key project we have been working on recently is with SIPEF Biodiversity Indonesia (SBI) in Sumatra. This is a biodiversity and conservation programme managed agribusiness SIPEF. Alongside expert consultants in Indonesia, we have been providing training on camera trapping methodologies to support the monitoring and protection of Sumatran tigers and other important species in SBI’s 12,672 hectares of licensed forest area, located in Bengkulu, Sumatra.

SBI have talked about the benefits of our work together so far:

“Since 2022, we have been collaborating with ZSL to enhance our biodiversity monitoring and management practices at the SBI concession. This partnership focuses on implementing scientific survey methodologies, including camera trapping, for monitoring the Sumatran tiger population, leveraging the expertise of ZSL and consultants at SINTAS. The initiative has markedly improved our wildlife monitoring capabilities, contributing to more effective conservation efforts. We deeply value the professional guidance received from ZSL which has been instrumental in advancing our efforts in protecting biodiversity.”

-- SIPEF Biodiversity Indonesia (SBI) on working with ZSL

This project provides a clear example of how conservationists and companies can work together to create stronger protection for wildlife in tropical commodity landscapes. Projects such as these are a key way to link company goals on biodiversity protection with tangible improvements in the field, and ZSL continues to seek opportunities to support commodity companies on the ground.

Visit our page to find out more about our advisory services or get in touch with us at sbf@zsl.org.