ZSL

Zoological Society of London

This guest blog was written by Miles Kempton, Visiting Scholar in ZSL’s Library and Archives. Read part 1.

Among the scientific job vacancies listed in British broadsheets and the journal Nature in December 1955, was a singular new position: ‘HEAD … OF THE TELEVISION AND FILM UNIT, Zoological Society of London and Granada T.V. Network Limited Ltd’. The successful candidate would have a ‘good degree in zoology and [be] competent to undertake the planning and supervision of the filming and televising of zoological subjects’—a rare combination of skills, particularly given TV’s infancy.1

Desmond Morris knew nothing of this opportunity when he travelled to Regent’s Park to meet the zoo’s charismatic scientific director, Leo Harrison-Matthews, that month. Morris was a high-flyer in the first generation of animal behaviour scientists trained by legendary Dutch zoologist, and future Nobel Prize winner, Nikolaas Tinbergen. In Oxford’s cramped zoology labs, Morris studied small animals, sticklebacks and tropical finches housed in makeshift aquaria and aviaries. He yearned for larger, more behaviourally flexible creatures like primates that Oxford simply could not accommodate. The Dutch ‘maestro’, as Tinbergen was affectionately known by students, pointed Morris to London Zoo.

Upon arrival, Matthews had disappointing news. Cash-strapped and under-resourced, the zoo could not support Morris’s research. Dispirited, Morris made to leave when, as he later remembered in his autobiography, Matthews ‘had a last-minute thought and … rummaged through some papers on his desk. “Have you ever done any filming?” he asked’. As luck would have it, Morris had: two short surrealist films, ‘one of which’, he told Matthews, ‘had won an amateur award and been shown on television’.2 Impressed, Matthews endorsed Morris to Solly Zuckerman, who thought him ‘first-rate’ on paper and was further encouraged after meeting him. Writing to Sidney Bernstein of Granada TV: ‘If there are others amongst those who have applied, who are anywhere near him, we need not worry about the fact that Attenborough is tied to the B.B.C.’ 3

Morris was not, however, without competition. Sifting through applicants, Matthews was keen to arrange an interview in New York with the entomologist, author, and lecturer, Lorus J. Milne. Unfortunately for Milne, there was one thing working against him: he happened to hail from North America. ITV was under fire for excessive ‘American influence’ and Granada management deemed it ‘unwise … to accept the appointment of an American [Milne, a Canadian, also held US citizenship] to such an important production post as the one we had in mind’.4

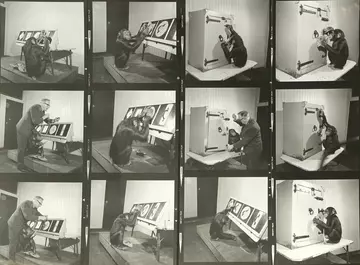

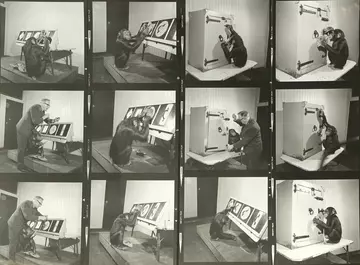

By the end of February, Morris had an offer. By accepting, he left a promising academic career behind for another in broadcasting. Granada had secured a director for the unit, but they were cutting it fine: in a little over three months, programmes would need to be one air. The pressure was on to get the unit up and running. Morris wasted little time building a team: his wife Ramona joined as programme researcher while Michael Lyster, a technician with photography experience in Tinbergen’s lab, came onboard as zoological technician. Cameraman John Shaw-Jones, experienced in documentary and instructional filmmaking, completed the quartet.

Two programme concepts emerged from these frenetic weeks to help Granada plug its scheduling gap in time for launch: a filmed evening show and a live children’s weekly. The latter, Zoo Time, became the unit’s longest-running and best-remembered production. Drawing on established studio-based formats, Zoo Time had much in common with existing natural history programmes on both sides of the Atlantic—Marlin Perkin’s Zoo Parade (1950–57 from Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago); a string of BBC series transmitted from London Zoo and presented by the likes of David Seth-Smith and George Cansdale; and the studio segments of Peter Scott’s new programme, Look (1955–69). But Zoo Time was not bereft of innovation. Morris was an ethologist—a scientist specialised in the study of behaviour from an evolutionary perspective—and a zealous one too. For Morris, Zoo Time was an opportunity to demonstrate and discuss this new science of animal behaviour for the next generation of potential ethologists watching at home.

The months wore on and, notwithstanding three episodes of an evening series called World of Animals cobbled together from Shaw-Jones’s footage, Zoo Time remained the unit’s only output. This singular focus on a children’s show was far from the lofty ambitions with which Bernstein and Zuckerman had dreamt up the unit, as we saw in Part I of this blog. Tensions ran high, with each side of this joint venture accusing the other of failing to live up to promises. Granada was wary of over-investing in expensive film production before much-anticipated advertising revenues flowed in. But their holding pattern could not last forever, and by the end of 1957, with a very real risk of the whole enterprise imploding, Bernstein agreed to invest heavily in filmmaking facilities.

The unit expanded, entering a new phase in which a team of cameramen accumulated many thousands of feet of footage. Editors cut this into TV programmes, as well as educational and research films, while zoologists projected footage at conferences and extracted stills for publications. Between the zoo’s vast collections, Granada’s resources, and Morris’s expertise, programmes explicitly focused on animal behaviour were becoming a regular feature on British screens.

1'Appointments Vacant’, Nature, 4496 (1955), p. 1277.

2Desmond Morris, Watching: Encounters with Humans and Other Animals (London: Max Press, 2006), p. 125. Morris produced both films with his future wife, Ramona Baulch, drawing inspiration from Luis Buñuel’s and Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou (1929). Clips from first, Time Flower (1950), can be watched online: ‘The Secret Surrealist: Desmond Morris’, BBC4, 5 April 2017, 22:28–24:00, <https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/0EA7774D?bcast=123875698>. The second film, Butterfly and the Pin. The Death of a Painter (1951), has not been located.

3Zuckerman to Bernstein, 21 January 1956, Solly Zuckerman Archive, University of East Anglia, ZOO/11/46/2/1.

4Denis Forman to Leo Harrison-Mathews, 17 February 1956, Zoological Society of London Archive, FIL/2/4.