This guest post is by Max Spokes, who spent part of summer 2021 researching in ZSL Library and Archives as part of a 'History of ZSL' project, in co-operation with the Institute of Zoology's Race, Ethnicity and National Origin (RENO) group.

Alfred Russel Wallace, Ali, and the new Standard Wing bird of paradise

On 24 October 1858, on the island of Bacan, a young Malay boy called Ali shot and took into his possession a bird which had been seen and in all likelihood shot for its plumage many times before by the local islanders.

He carried the bird on his belt, along with several others, and whilst on his way back to camp, showed the specimen to his employer and companion, Alfred Russel Wallace.

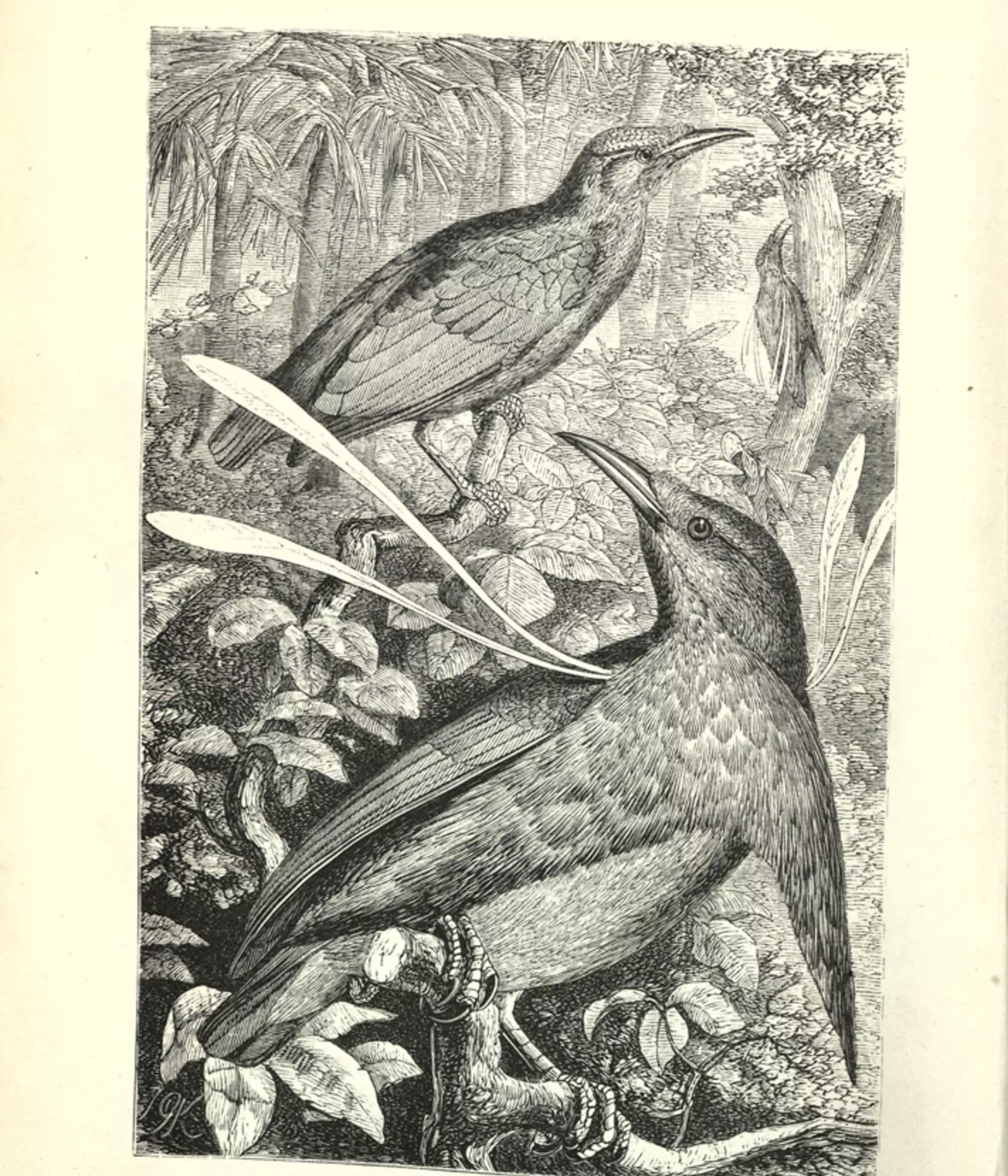

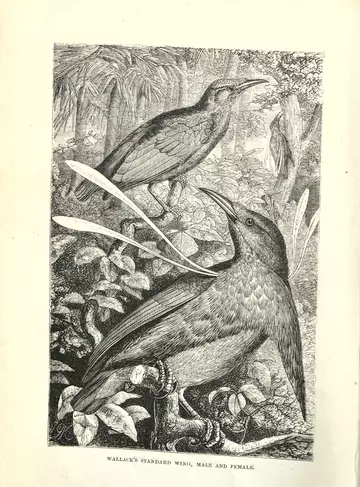

Wallace described the bird’s ‘mass of splendid green feathers on its breast, elongated into two glittering tufts’, and remarked on a ‘pair of long white feathers, which stuck straight out from each shoulder.’

In the passage describing his ‘discovery’ of a bird of paradise new to Western science in his book, The Malay Archipelago, Wallace explains that ‘Ali assured me that the bird stuck them [white feathers] out this way itself, when fluttering its wings, and that they had remained so without his touching them.’

And thus, armed with this piece of behavioural information, Wallace proclaimed, ‘I now saw that I had got a great prize, no less than a completely new form of the Bird of Paradise, differing most remarkably from every other known bird.’

The bird which, in 1859, was named Wallace’s Standard Wing bird of paradise (Semioptera wallacii) was then, ‘discovered’ by Ali, only for his find to be later accredited to Wallace, and for the bird even to be named after him.

Searching through Zoology's history

During research which I conducted for my undergraduate history dissertation in the summer of 2021 at the ZSL’s Library, I came across many instances in The Malay Archipelago especially of this kind of appropriation of discovery and knowledge, often un-or under-remunerated, yet perhaps none were so blatant as Wallace’s taking credit for the discovery of ‘his’ Standard Wing.

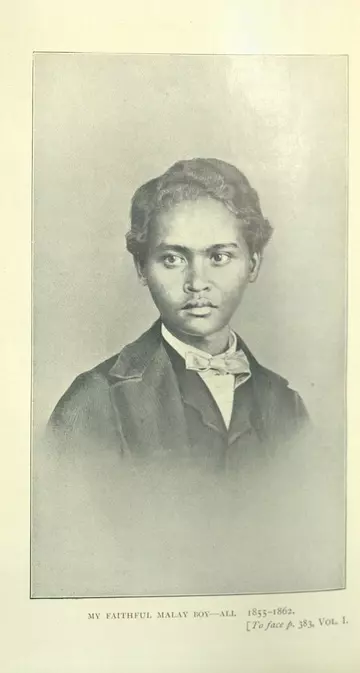

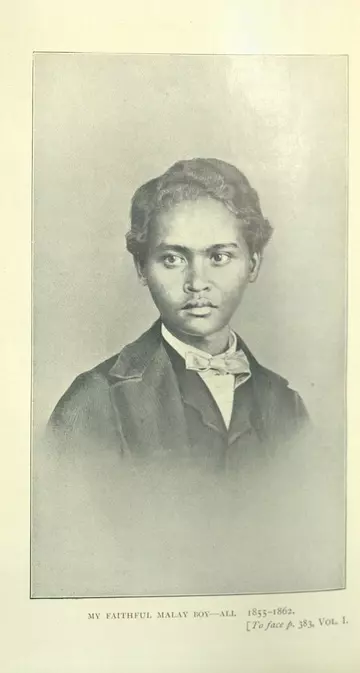

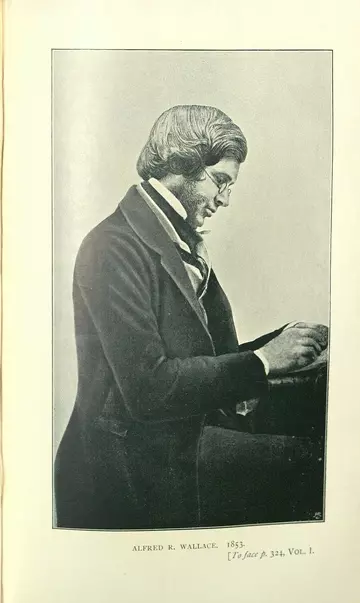

Ali and Wallace’s relationship was an interesting and nuanced one: Ali was employed by Wallace in Sarawak in 1855, near the start of Wallace’s eight-year expedition in the Malay Archipelago (1854-62). Ali remained in Wallace’s company right up until Wallace’s departure back to England in 1862, and was praised as Wallace’s most ‘faithful companion’ in his memoir, along with a full-page portrait.

Colonialism and empire in zoology

For all the mutual affection they had for each other – Ali would even later describe himself as ‘Ali Wallace’ to an American zoologist in 1907 – it is important to recognise how Wallace – as was standard of the time – minimised the agency and vital scientific contributions made by Ali.

Whilst Wallace describes in The Malay Archipelago how Ali initially brought him what later became known as Wallace’s Standard Wing bird of paradise, later on in the book he claims that the bird was ‘discovered by myself in the island of Bacan’.

And then, later on in a scientific presentation to the ZSL about his general search for birds of paradise (not specifically the Standard Wing), Wallace gives no mention of Ali, even though Ali would have accompanied Wallace and been an important contributor to this ‘search’.

Ali therefore starts off in The Malay Archipelago as a character who features frequently in Wallace’s descriptive passages, but whose role in collecting specimens is then diminished by Wallace, and whose name eventually is left out altogether in the scientific discussion about the fieldwork undertaken to find various birds of paradise.

As I explore in much greater depth in my dissertation, what lays behind this minimising of Ali’s role is a complex web of ideas about race, empire, and who qualifies to be a scientist, and who, just as importantly, does not.

Whilst Ali contributed not only in the specimens he collected but also in the information he provided about species’ behaviours and other valuable observations, his contributions to Wallace’s eight years in the Malay Archipelago have been minimised and diminished (by Wallace and historians).

Indeed, one Wallace historian, Michael Shermer, characterises Wallace as ‘a one-man collecting machine.’ As the example I have explored in this blog shows, this is simply not the case, and only perpetuates the misleading picture of the one-man Western naturalist, single-handedly navigating tropical lands and discovering hundreds of new species in the process.

This has important implications to this day, regarding modern conservation efforts, which too often marginalise indigenous and local peoples, failing to include their vital expertise and knowledge of ecosystems and species.

There are, I am sure, hundreds of more stories like Ali’s which deserve to be told, residing in the books, journals, diaries, and letters stored in the ZSL Library’s catalogue; I am extremely grateful to Ann and Emma for allowing me to access the library’s archives in order to shine a light on Ali, and to use his example to construct my wider argument about natural history and empire in my dissertation.

This guest post is by Max Spokes, a former student at Balliol College Oxford. Max spent part of summer 2021 researching in ZSL Library and Archives as part of a 'History of ZSL' project, in co-operation with the Institute of Zoology's Race, Ethnicity and National Origin (RENO) group. The RENO group is part of the Science Directorate Equality, Diversity and Inclusion committee. Max researched some of the 'hidden' contributors to the work of Lucy Evelyn Cheesman, a former Curator of Insects at ZSL. He also looked at those contributing to the work of ZSL Fellow, Alfred Russel Wallace. In this blog he identifies some of the contributions of Ali who assisted Wallace. As this is the bicentenary year of Wallace's birth, it seems an appropriate time to celebrate his contributions together with those of his associates.

Max is now studying for a Masters in Anthropocene Studies at the University of Cambridge.

References

- A. R. Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, 10th edn (Singapore, 2008), p. 251.

- Ibid.

- A. R. Wallace, My Life: A Record of Events and Opinions (2 vols, London, 1905), i, p.383.

- J. Van Wyhe and G. M. Drawhorn, ‘“I am Ali Wallace”: The Malay Assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace’, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 88/1 (2015), p. 26.

- A. R. Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, 10th edn (Singapore, 2008), p. 429

- M. Shermer, In Darwin’s Shadow: The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace (Oxford, 2002), p. 126.