Ann Sylph, MSc, MCLIP

ZSL Librarian

Guest blog by Miles Kempton, Visiting Scholar at ZSL's Prince Philip Zoological Library & Archives.

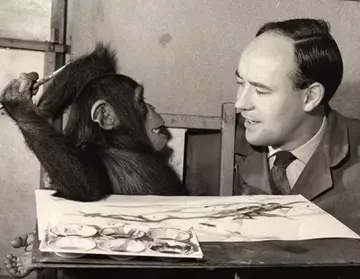

In December 2019, London's Mayor Gallery exhibited 55 paintings and pastels by a late artist known simply as Congo. Expectations were high: three of Congo's paintings had outsold Andy Warhol at a Bonhams auction in 2005, fetching more than twenty times their estimate. Moreover, at the peak of Congo's fame in the 1950s, superstar artists, scientific luminaries, and even royalty had clamoured to acquire his works - Juan Miro, Pablo Picasso, Julian Huxley, and Prince Philip, to name but a few. Congo's illustrious list of collectors is all the more impressive considering that he was a chimpanzee at ZSL London Zoo - the most famous, in fact, of the 'picture-making apes' studied by the zoologist, surrealist artist, and broadcaster, Desmond Morris. The recent resurgence of interest in Congo's pictures invites the question: what is the abiding appeal of paintings by an animal?

Picture-making monkeys and apes were nothing especially new when Congo first made a splash in 1957. Russian and American scientists had studied the phenomenon , albeit unsystematically, in the early twentieth century. But their research rarely moved outside the pages of specialist journals or scientific textbooks. To understand Congo's rise to international stardom, we need to look at what had changed by the 1950s. Three factors are important here. First and foremost: timing. Congo's paintings hit the headlines when new movements in the avant-garde were causing a stir. It was precisely because Congo's paintings looked like those of the controversial 'abstract expressionists ' (think Jackson Pollock) that they were fodder for a media frenzy. Second: television. Fast emerging as Britain's dominant mass medium, television gave Congo and Morris enormous reach. With newspapers and magazines feeding off TV's growth, Congo became a household name in the late 1950s and 1960s. Third: science. Desmond Morris put Congo at the very centre of his efforts to understand art as a biological phenomenon. This gave Congo a compelling dual identity- TV personality on the one hand, scientific research animal on the other.

Congo's story began on the small screen. On September 22 1955, Britain's burgeoning television audience learned of a new 'tingly fresh' toothpaste. This was momentous stuff; not the toothpaste, but the advert - the first to appear on British screens. It heralded the launch of Independent Television, a new privately-owned rival to the BBC. For the first time in British history, broadcasting was competitive. Within weeks, ITV's franchise for the North, Granada TV, had finalised a contract with the ZSL to establish a Film and TV Unit at ZSL London Zoo. The unit, a world first, was headed by Morris, who also hosted its flagship programme for kids, Zoo Time (1956-68). Morris chose Congo as Zoo Time's mascot and the chimp quickly became the show's most popular animal personality. As Congo's on-screen popularity grew, Morris began his private investigation into the biological roots of art.

Morris was fascinated by the search for the genesis of artistic creativity. By the 1950s, psychologists, philosophers, anthropologists, and art critics all had ideas about where to look. Perhaps the answer lay in the earliest scribbles of children? Or in the art of so-called 'primitive' peoples? Perhaps the prehistoric cave paintings of Lascaux held the key? Whatever their preferred subject, scholars perceived that pictures by children, 'primitive' societies, and prehistoric peoples were insightful because of their simplicity. They believed that traditional Western art, with its formal conventions and technical sophistication, carried too much history to be of much use. Here is where Morris and Congo fit in. Why not see what happened when you gave paintbrush and paper to our nearest living relative? Surely this was the ultimate test of primordial aesthetics?

For three years, Morris studied how Congo worked with different artistic media: blank sheets of paper and pencils, paper pre-marked with shaded or unshaded shapes, different coloured paints and paper - all were grist to Morris's mill. All told, Congo produced some 400 pictures between 1956 and 1959 before his interest in art began to fade. Crucially, throughout the entire experiment Morris never encouraged or rewarded Congo, the activities were rewards in themselves. Morris presented his work at scientific conferences in the late 1950s and brought everything together in his fascinating 1962 book, The Biology of Art.

What did commentators make of it all? Responses to Congo's first exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in September 1957 were mixed. For the cynics, the show was symptomatic of the degeneration of modern art and shameless commercialism. Just because 'certain humans during the past 20 years have chosen to paint like psychotics', fulminated one reader of the New Statesman, 'hardly justifies a prestige organisation in selling the reflex twitching of apes at ten guineas a throw' [1]. The Evening News observed, 'for years past, we have been offered in art galleries... compositions differing not a whit from those of the amiable and devoted young chimp'. The author continued, 'we wonder: are the monkeys becoming more human or is man becoming more ape-like [2]?'The Daily Telegraph was more sympathetic, acknowledging the scientific interest of the exhibition and even praising the 'originality and freshness' of Congo's paintings [3]. In spring 1958, the plot thickened when Congo's paintings crossed the Atlantic for an exhibition in Baltimore. Works of art were usually exempt from import duties, but there was a snag. As the Daily Express and a host of British papers reported, US customs officials deemed that paint 'placed on canvas by a sub-human animal with no rational mind or powers of imagination does not meet our test for works of art' [4]. Much of the reportage was tongue-in-cheek. But at its most solemn, the public discussion aroused by Congo's pictures hinged on whether art was a uniquely human aptitude. Was Morris right when he argued in The Biology of Art, that art was part of our apish inheritance? Or did Congo merely exhibit the 'reflex twitching' of a 'sub-human animal', totally different in kind from works of the human hand? The debate rumbles on and Congo periodically resurfaces to remind us of this remarkable episode at the intersection of art and zoological science.

[1] "Correspondence," New Statesman, October 12, 1957.

[2] "The Higher Primates," Evening News, July 26, 1958.

[3] "Chimpanzees' Art on Show," Daily Telegraph, September 17, 1957.

[4] Daily Express, May 9, 1958.

Further reading

Lenain, Thierry. Monkey Painting. London: Reaktion, 1997.

Morris, Desmond. Watching: Encounters with Humans and Other Animals. London: MAX, 2006.

Morris, Desmond. The Biology of Art. London: Methuen, 1962.

Morris, Desmond. The Story of Congo. London: Batsford, 1958.

Schiller, Paul H. "Figural Preferences in the Drawings of a Chimpanzee." Journal of Comparative Physiological Psychology 44, (1951): 101-11.

For more about Miles Kempton and his research, our guest blogger and ZSL Library Visiting Scholar, take a look at his page at Open-Oxford-Cambridge Doctoral Training Partnership. You can follow Miles on Twitter @kempton_miles