Ann Sylph, MSc, MCLIP

ZSL Librarian

Guest blog by David A. Lowther, former Visiting Scholar at ZSL's Prince Philip Library and Archives.

In common with many nineteenth-century amateur naturalists, Brian Houghton Hodgson (1801-1894) is an obscure name today. Lost in Darwin's shadow, and for much of his active working life stationed far away from the centres of European science, Hodgson's later reputation has long been that of a 'colonial' collector, who supplied better-qualified naturalists (like Darwin) with the raw materials to transform man's understanding of the natural world.

Hodgson was indeed a collector, but one who worked on an extraordinary scale and often in challenging circumstances. As an East India Company diplomat, Hodgson was posted to Nepal between 1820 and 1843. During this time he became fascinated by the region's animals. He used the opportunities provided by his position to begin amassing a huge number of zoological specimens, from skins and skeletons to a growing number of live animals that he kept in a specially built menagerie in the Residency grounds. His collectors, mostly from the Kathmandu Valley, ranged far across the Himalayas in search of new or poorly understood species. Their industry, and Hodgson's apparently insatiable curiosity, resulted in some 9,500 identifiable specimens passing through the British Residency. As Hodgson later donated or exchanged many of them with other naturalists, this total likely originally stood far higher. He also collected paintings of animals, commissioning and eventually amassing some 3,000 of them.

The credit for the paintings rests with a small group of Nepalese artists. Relatively isolated in Kathmandu, Hodgson was forced by circumstance to hire local artists, who worked under his supervision. It is not known exactly how many artists worked for Hodgson between 1824, when he began his zoological studies, and 1843, as most of their names have been lost. The identities of only two remain: Tursmoney Chittakar, who signed at least one painting, and Rajman Singh, who appears to have become Hodgson’s most favoured artist by the early 1830s and who was the most skilled of all. Quite how skilled can be appreciated only when we consider that painting animals in this way was wholly alien to Nepalese tradition, and that Singh and his fellow chitrakars would have previously been employed painting Buddhist and Hindu devotional imagery and abstract mandalas.

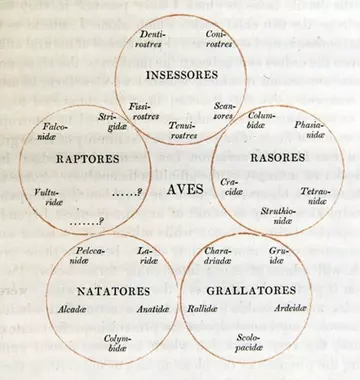

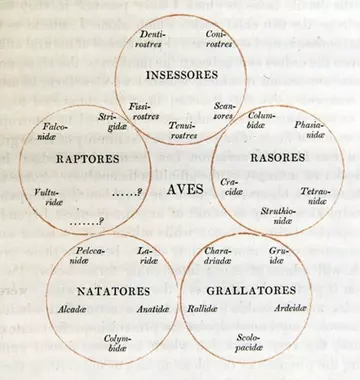

Hodgson had plans for his paintings. Despite his isolation in Kathmandu, he was well-aware of the heated debates about zoological classification then erupting in Britain’s scientific societies. He became fascinated by a new system called Quinarianism, devised in the early 1820s by a group of British zoologists including the Zoological Society’s first Secretary, Nicholas Vigors. Classifying all living organisms in groups of five, Quinarianism portrayed a stable natural order. Hodgson would later become a supporter of Darwin’s evolutionary theory, but during the 1830s and early 1840s he stuck with Quinarianism, even as it began to be rejected by his fellow naturalists.

Hodgson planned to publish a huge, multi-volume ‘Zoology of Nipal’, ordered according to the Quinary System and illustrated using his paintings. Lacking business skills, and remote from the publishing centres of London and Calcutta, he sought assistance from British naturalists with whose views he agreed, and who had a proven track record of publishing success. Between 1836 and 1843, he approached a succession of these naturalists – John Gould, William Swainson, Nicholas Vigors -, all with the same disappointing result. Eventually, he dropped his plans, partly due to political problems in Nepal and his conflict with the Governor-General of India, Lord Ellenborough, who eventually sacked him in 1843.

Although Hodgson lived in Darjeeling until 1859 and continued his zoological work, he never again tried to publish his paintings. He returned to Britain and in 1874 donated half of his paintings to the Zoological Society. The rest went to the British Museum. Thankfully, the paintings have recently begun to attract attention once again – not only for what they tell us about one of the great nineteenth-century naturalists, but as a window onto colonial science, and the practices of collectors at a crucial period in the history of zoology.

Further Reading

Read David's paper in Archives of Natural History Patron’s review: The art of classification : Brian Houghton Hodgson and the “Zoology of Nipal” David A. Lowther Archives of Natural History 46.1 (2019) pp. 1-23

Use our online catalogue to access the scanned manuscripts of Brian Houghton Hodgson