ZSL

Zoological Society of London

This guest blog was written by Miles Kempton, Visiting Scholar in ZSL’s Library and Archives

In August 1955, the ZSL’s new secretary Solly Zuckerman read an intriguing proposal. His friend, the cinema magnate and commercial TV executive Sidney Bernstein, wanted to team up to establish a TV and film unit in London Zoo. The unit, Bernstein promised, would be ‘the most perfect possible tool for zoological film research’—and a money-spinner to boot. Bernstein’s was a particularly compelling proposal, and the latest in a series of approaches from TV companies since the Television Act (1954) broke the BBC’s monopoly on broadcasting and laid the groundwork for Independent Television (ITV). In this two-part blog, I chart how ZSL navigated the new landscape of competitive broadcasting, why it settled on Granada, and what this meant for natural history broadcasting in the UK.

In the years before Bernstein’s letter to Zuckerman, while MPs, pressure groups, and advertising interests wrangled over commercial TV, wildlife was thriving on the BBC. Drawing on a tradition of cinematic travelogues, Armand and Michaela Denis channelled the thrill of the imperial hunt for the small screen, replacing the gun with the camera in pursuit of African big game; Peter Scott offered more cerebral studio-based programmes from Bristol in the mould of the gentlemanly amateur naturalist; and David Attenborough was making a name for himself as host of Zoo Quest, another travelogue-style programme which followed the exploits of joint BBC and ZSL animal collecting expeditions.

These programmes had broad appeal as wholesome family viewing, seamlessly fulfilling the BBC’s public-service agenda to inform, educate, and entertain. To commercial TV executives waiting in the wings, it was clear that animals made excellent TV. Among them was Sidney Bernstein who had recently formed Granada TV with his brother, Cecil. The emerging ITV system comprised a network of regional programme companies, and together the Bernstein siblings had won the franchise for the North of England.

Sidney Bernstein’s letter to Zuckerman was carefully crafted to appeal to ZSL. He envisaged a team headed by a ‘qualified zoologist, acceptable to the Society’ and at least two cameramen whose ‘first duty would be to provide film research material for the Society’. Even better, Granada would assume all liabilities and ZSL would receive a share of the resulting revenue, which Bernstein suggested would probably be ‘substantial’1.

Zuckerman responded instantly with two terse sentences: one expressing interest and another asking for a minimum annual figure2. This is worth emphasising. Historians have been tempted to downplay the financial incentive of Bernstein’s approach, but a deal with Granada promised lucrative returns just when ZSL needed them most3.

The ravages of war and postwar austerity left London Zoo in desperate need of funds. One architect’s survey found barely 10–15% of buildings to be fit for purpose and ambitious reconstruction plans were afoot4. Granada’s offer amounted to a guaranteed £3,500 per annum (just over £75,000 in today’s money) and a 50% share in profits generated by the distribution of films produced by the unit. Against the modest returns generated by existing contracts with the BBC and other film companies this was an attractive offer; these other deals amounted to only £802 in 19555. But the real meat of the proposal lay in the profit-sharing option, which seems to have been decisive.

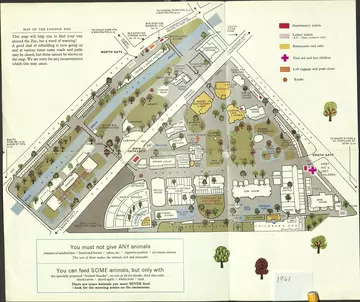

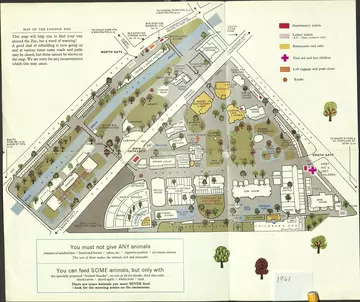

However attractive Granada’s offer, ZSL needed to tread carefully. A national institution presiding over the world-famous London Zoo and a pioneering wildlife park in the Dunstable Downs, ZSL could hardly afford to enter an exclusive contract with one broadcaster at the expense of others. But keeping the gates open to all and sundry production crews in the age of competitive broadcasting would create an impossible situation, upsetting paying visitors, disrupting scientific work, and jeopardising standards of animal care. A compromise was needed.

The solution came by inserting a special clause in the contract with Granada: any zoo fare deemed to be of national significance - unusual births, exciting animal acquisitions, and so on - could be covered by any broadcaster, while everything else needed the green light from Granada. As it emerged in practice, the agreement gave Granada quasi-exclusive broadcasting rights to ZSL’s collections.

With broad terms agreed and each party’s lawyers busy drafting heads of agreement, the race was on to get a unit up and running in time for the launch of Granda’s service in May 1956. First things first, the unit needed a director, trained in zoology and comfortable in front of the cameras. A promising candidate turned up at Regent’s Park in December 1955, but for quite different reasons.

Desmond Morris, a postdoctoral researcher at Oxford specialising in animal behaviour, wanted to study London Zoo’s primates. The zoo couldn’t support his research - it simply didn’t have the money - but it did have another opportunity that might appeal to this charismatic young scientist.

Read part 2 of this blog where we pick up the story with Morris’s job interview and the frenetic months before and after the curtains went up for Granada.

1Bernstein to Zuckerman, 29 August 1955, Zoological Society of London Archive (ZSLA), FIL/1/2.

2Zuckerman to Bernstein, 29 August 1955, ZSLA, FIL/1/2.

3In his excellent study of BBC wildlife films, historian Jean-Baptiste Gouyon chose to emphasise the concerns of ZSL officials that Attenborough’s growing prominence on Zoo Quest overshadowed the scientific contribution of ZSL: Gouyon, BBC Wildlife Documentaries in the Age of Attenborough (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 64–66.

4Eirwen Owen, ‘The Zoological Society of London 1929–1976’, (unpublished manuscript, October 1984), Solly Zuckerman Archive, University of East Anglia, ZOO/12/11. [There is also a copy of this manuscript in ZSL’s Archives]

5Zoological Society of London Annual Report, 1955, ZSLA, REP/1/22, p. 48.