Reptiles and climate change

Would reptiles thrive on a warmer planet? Dr Monika Böhm, from ZSL's Institute of Zoology, on the research into climate change vulnerability in reptiles.

Reptiles – they like it hot, right? Famously ectotherm – meaning they depend on external sources of heat to warm up their bodies to go about their day-to-day business – surely warmer is better for reptiles. I mean, they like deserts, right?

Burrowing reptiles, such as this species of worm lizard, may be buffered from the effects of climate change by burrowing into the soil.

Well, true, some reptiles inhabit desert environments – for example, lizard species richness is very high in the baking interior of the Australian continent. But then large numbers of reptile species also occur in the tropical forests of the world.

Fact is that the 10,272 species of reptiles currently described (as of August 2015, but scientists find new species nearly daily: according to The Reptile Database, nearly 250 species were added from 2014 to 2015) occur across pretty much all environments and habitats our planet has to offer, with the exception of the Antarctic continent and the Arctic.

Reptiles occur in tropical forest, savanna, grassland, and yes, also in deserts. And there are freshwater and marine species too – think turtles and sea snakes!

And yes, reptiles rely on external heat to slither or crawl about their business. But even reptiles have their limits. Just like our bodies stop functioning properly when body temperature gets too high, the same goes for reptiles.

As a result, and because they cannot themselves regulate their temperature like we endotherms can, reptiles may be highly sensitive to climate change and the increasing temperatures and water stress that can come with it.

Climate change threatening reptiles

So do we know how many reptiles are threatened by climate change? Well, not really. Climate change is an emerging and often slow-acting threat, potentially affecting species over long(ish) time periods - we have only recently started to get a handle on assessing the severity of this threat to biodiversity.

For example, using data on current climatic conditions experienced by species throughout their range, and combining this with future climate predictions provided by climate scientists (for example the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), we can assess how species ranges may change due to changing climate.

Similarly, we can check whether species have certain biological traits or are associated with certain environmental characteristics which may make them more vulnerable to the effects of climate change – an approach we refer to as a trait-based assessment.

Last week, we published the first such trait-based assessment for a global representative sample of 1,500 reptiles – the same sample we previously used to estimate extinction risk levels in the group. This previous study showed that one in five species of reptile are threatened with extinction – with levels in turtles and tortoises and freshwater systems estimated much higher.

Our most recent study is trying to complement our previous findings. For this, we used a trait-based assessment approach advocated by our partners at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), specifically by their climate change unit.

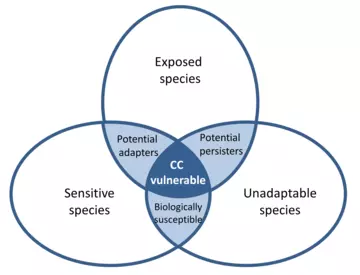

In a nutshell, by assessing species across three dimensions of vulnerability (their sensitivity to climate change, their adaptability to changing conditions and their exposure to a changing climate), we can get an estimate of the most vulnerable species: those species which are simultaneously sensitive and exposed to climate change and have low adaptability.

Overall, 22% of species were found to be highly vulnerable to climate change. In fact, when considering only climate change sensitivity, around 80% of reptile species were considered sensitive to climate change, again showing – that reptiles on the whole don’t actually “like it hot”!

Interestingly, species vulnerable to climate change did not overlap much with those listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (the system we use for estimating extinction risk of species). Why is this interesting? Well, decisions about spatial conservation priorities are often based on the distribution of threatened species (those in the categories Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List). But hotspots of species with high climate change vulnerability do not always overlap with these hotspots of threatened species richness; we found climate change vulnerable species particularly in northwestern South America, southwestern USA, Sri Lanka, the Himalayan Arc, Central Asia and southern India. This suggests that – on top of spatial priorities dictated by threatened species distributions – we have to prepare for additional spatial conservation priorities in the face of a changing climate.

However, our study is only a first stab at figuring out how affected by climate change reptiles might be. Assessments like these are very data hungry – data gaps are therefore the norm! And with the amount of species we are ultimately trying to assess, filling these data gaps requires a much more concerted effort, engaging with field herpetologist to secure the best possible data on species and making trait databases openly available to experts for scrutiny, thus helping us to improve our data and knowledge about climate change and reptiles (our data is available online).

Atheris certaophora - vulnerable on the IUCN Red List - was assessed as biologically susceptible to climate change, but - due to a relative lack of exposure - not as highly vulnerable.

Additionally, there are still issues to be overcome with regards to the assessment methods. For example, in many cases, we do not really know where the threshold might be between high and low sensitivity, adaptability or exposure – so we are relying on somewhat arbitrary thresholds to break our continuous low-to-high spectrum into low and high vulnerability. To address this, we employed different thresholds for a number of traits to examine how this might change the overall outcome. But ultimately, we require some sort of ground-truthing of our data – data from the field showing the link between certain traits and climate change vulnerability – to further develop the assessment process. Which in turn brings us to another issue: not all traits are necessarily connected to climate change vulnerability across all species.

Some species may show some behavioural adaptation to reduce vulnerability to climate change: for example, nest site choice – for example using a shadier nesting site - can buffer against adverse climate effects in species with temperature-dependent sex determination. And so what is detrimental to one species might not necessarily be detrimental to another (which is of course good news for some species). And lastly, how good is a sample of 1,500 reptile species to assess climate change vulnerability of this species group in the first place?

So these are the questions we are now focussing on, in collaboration with our friends at the IUCN and reptile experts worldwide – we are definitely not twiddling our thumbs! In fact, reptile conservation as a whole is moving forwards in leaps and bounds. An entire special issue is about to be devoted to the topic in the journal of Biological Conservation, featuring contributions - including the above - from ZSL research. It’s great to see these fascinating but previously vastly overlooked creatures starting to take centre stage in the conservation world – because reptiles in our rapidly changing world really can become as “hot and bothered” as the rest of us!

As the original science-led conservation organisation, our unique insight and evidence-based approach achieves positive change and powers sustainable, innovative solutions that work, for wildlife, people and the planet.